The Politics of Refugee Visa Refusal

For Johnson, as with all things, party management comes first. With PartyGate in abeyance thanks to the Met's intervention, it is going to come back regardless of what happens in Ukraine and he needs as many backbenchers on side if he's to survive the fallout. And those Tory MPs don't share the public's enthusiasm for a humanitarian gesture. The reliably awful Daniel Kawcsynski, for instance, argues offering refugees sanctuary "is immoral". They should stay in countries near to Ukraine so they can readily travel back once the war is over. This view is by no means a minority one, and echoes a line we've heard many time from front benchers: Britain meets its obligations by giving generously to countries housing large refugee populations. Johnson isn't about to challenge a commonsense he himself supports if it means putting MPs' noses out of joint, so he won't.

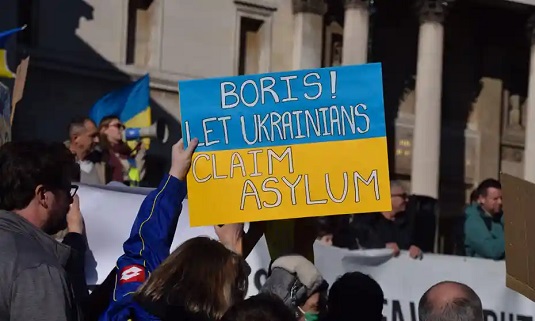

It's not just about keeping the parliamentary party sweet. As far as the Tories are concerned, Ukrainians are the wrong type of refugee. A lot has been made recently of the unsubtle racism of the press and establishment about how war "isn't supposed to happen" in Europe, but we've seen the Tories willing to take in something like 106,000 people who've left Hong Kong. Compare this with their lack of enthusiasm to help Afghans fleeing the Taliban and we get nearer to the nub of the issue. It's about class. In the Tory imaginary, the Hong Kong'ers are entrepreneurial and more likely to have assets to their name. They speak fluent English and, politically, those making the journey are going to be right wing and anti-communist. A small but useful future constituency for the party that has offered them refuge. Ukrainians, like Afghans, do not. Most are women, working class, and likely to be travelling with dependents. Immigration minister Kevin Foster's suggestion that Ukrainians should apply to be fruit pickers betrayed the class frame the Tories are applying to this issue. The "strains" they will place on underfunded public services is not the reason, what is is a perceived vulnerability on their right flank. Farage is on his anti-green grift for the moment, but could quickly pivot to refugees if he thinks the political profits are there.

Does that explain everything? Again, no. While the Tories have tied themselves in knots over it, Labour hasn't covered itself in glory either. Yvette Cooper has been on the news, doing her overrated best to turn the visa issue into a matter of process. The problem, Cooper says, isn't the Tory refusal to waive visas, but that the visa office in Brussels should extend its opening hours. It's almost as if the shadow home secretary has form for this sort of thing. Again, looking at the polling and taking those lectures about being on the side of the public at face value, why have Labour joined with the Tories in an effort to ignore the popular mood?

It's a matter of what Johnson and Keir Starmer share: an authoritarian politics. Each has a different base. For Johnson, authoritarianism is the necessary flipside of his populism and is entirely crucial to the Tory project generally. For Starmer, as a manager accustomed to managerial habits the Fabian tradition with its emphasis on elite-led policy making and the Labour right's interminable preoccupation with protecting its factional advantages resolves itself in a politics concerned with rebuilding reverence in state institutions and, above all, the leader. Both leaderships have an interest in refusing public demands, simply because a concession on Ukrainian refugees green lights the idea both can be shifted by popular opinion. Consider PartyGate again, for example. Tory MPs haven't no-confidenced the Prime Minister (yet) because doing so under mass pressure sets a dangerous precedent. Starmer resisted hitching himself to the bandwagon for as long as he could get away with, subtly suggesting he would expect a quid pro quo from Tories alert to this sort of thing should he be subject to similar strain.

This is brittle politics. It shows how shallow both their projects are because they know they cannot be defended on their merits. Instead they have to affect a distance from the public mood every bit as wide as Putin's ludicrous table, even if accepting more refugees results in short term popularity. Opinion is fickle and can turn, so keeping to the status quo suits them fine: politics is narrowed to the point where both can police and define the terms of discourse, something the Tories normally rely on the press to do while Starmer has actively pursued this through his own party. It seems strange that denying public opinion is a sign of weakness, but what it shows is how, underneath all the blustering and posturing, mainstream politics in this country fears for itself.

Image Credit